Torrey Pines High School student Daniel Cai, intern at La Jolla Institute for Immunology

Daniel Cai is a senior at Torrey Pines High School, in San Diego County. He’s also one of the few people to have witnessed the onset of an autoimmune skin disease called pemphigus vulgaris.

“It started around two years ago—right before the pandemic. My mom was showing these symptoms. She was coughing up blood, and there were these lesions popping up all over her body,” says Cai.

“We went to her primary care doctor, to ENTs and even dermatologists, and we still weren’t getting good advice. We weren’t getting the right diagnosis. That was a really hard period of time,” he recalls. “At one point, my mom’s condition was deteriorating and the lesions were not getting better. The lesions in her mouth meant she couldn’t speak. She couldn’t eat or drink without medication.”

Cai’s mother was eventually diagnosed with pemphigus vulgaris, a chronic autoimmune condition that leads to blisters on the skin, mouth and throat. The disease is excruciatingly painful and can be fatal if a sore becomes infected.

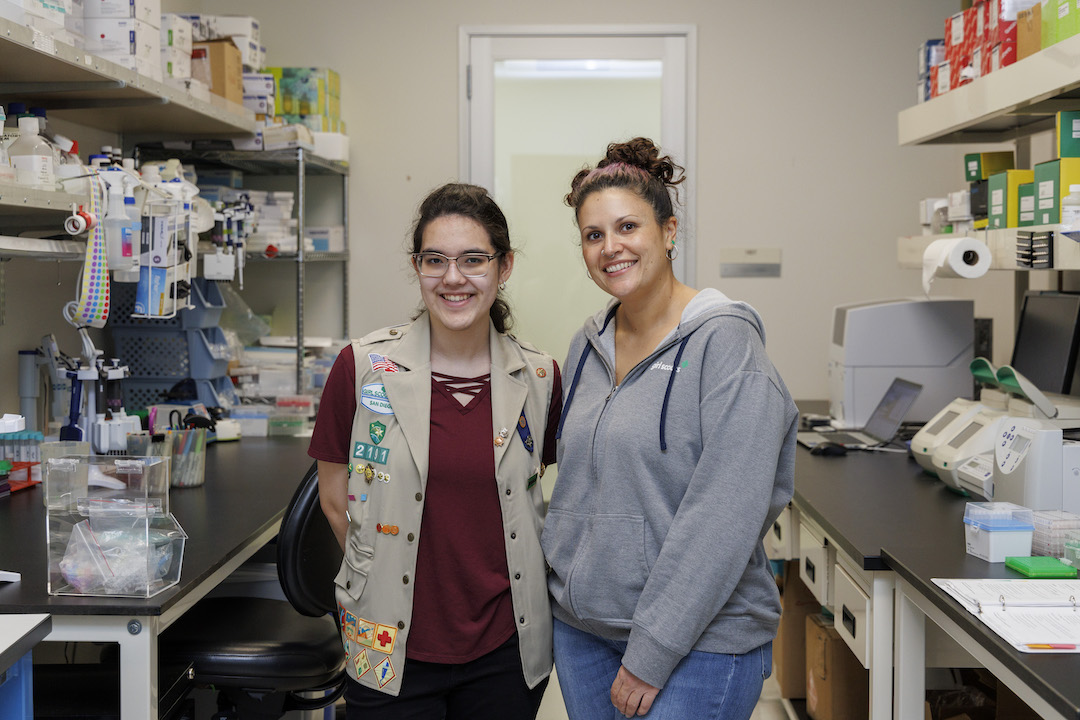

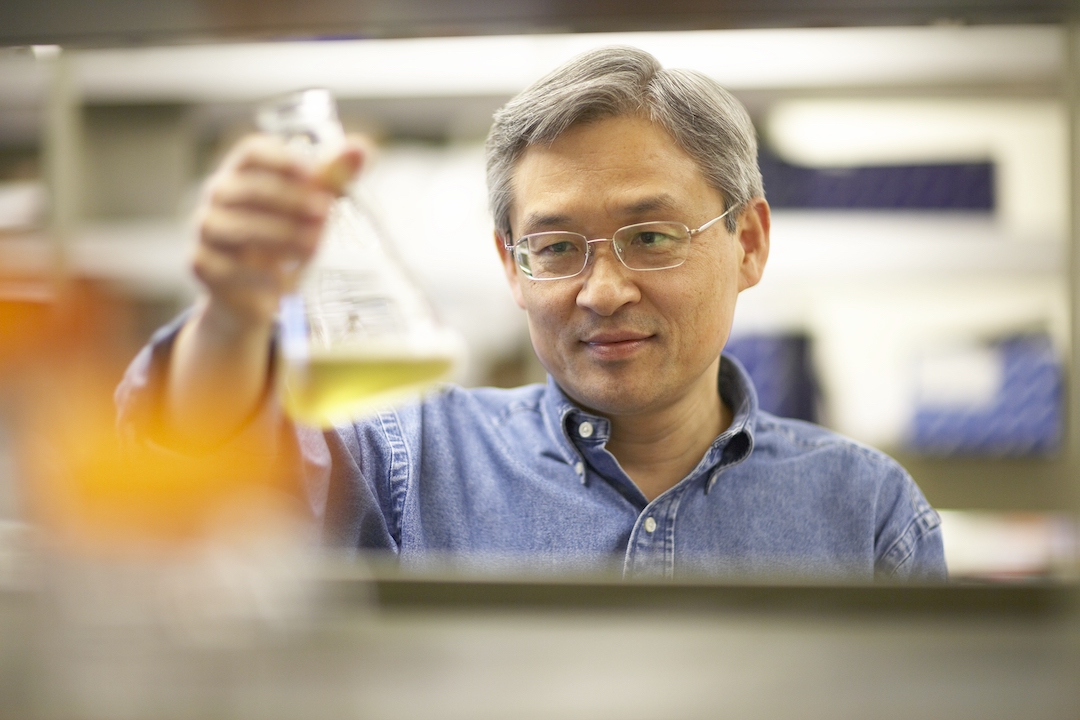

Today, Cai is conducting his own research as an intern in the lab of La Jolla Institute for Immunology Associate Professor Ferhat Ay Ph.D., a leader in the use of bioinformatics and computational tools to study the immune system. With Ay’s support, Cai is developing a computer-aided diagnostic tool for diagnosing autoimmune blistering diseases (AIBDs).

Cai’s work recently caught the attention of the Society for Science, which named him a top scholar in the prestigious Regeneron Science Talent Search 2022. Cai’s hope is that doctors could use his program to help them find answers when they encounter patients like his mom. So far, his well-honed algorithm performs on par with dermatologists’ diagnostic accuracy.

Cai describes himself as a curious person. He’s always been interested in computer programming and artificial intelligence. He even interned earlier in high school at an artificial intelligence startup.

As his mom’s condition slowly improved with treatment, an idea came to him: He wanted to use artificial intelligence to help other people with pemphigus vulgaris. “My family has access to medical care, but for other people around the world who don’t have access, a diagnostic delay could be even worse,” says Cai.

So Cai began emailing scientists across the country with his idea. He didn’t have high hopes. “I knew I was just a highschool student. I wasn’t doing groundbreaking research,” says Cai. “LJI surprised me with their response. Even the LJI researchers who couldn’t help me were really supportive and said they liked my initiative.”

Several LJI scientists started brainstorming with him and sharing advice. By Fall 2021, Cai had developed an initial prototype and found an internship in Ay’s lab, where he could continue exploring how immunology and computer science connect.

Through trial and error, Cai has designed an algorithm that takes in data from images of skin conditions. The algorithm learns which details from an image correspond with features of different diseases, and it can begin suggesting diagnoses based on new images it sees.

This “machine learning” approach is becoming more and more useful in healthcare. Researchers have designed algorithms to diagnose glaucoma, breast cancer, liver diseases and more. These tools have proven especially useful for diagnosing dermatological conditions, such as melanomas, which are easily photographed at home or in a doctor’s office.

Cai’s algorithm focuses on autoimmune blistering diseases. The first problem he faced was that these rare diseases aren’t photographed every day. “It’s extremely rare,” says Cai. “And on top of that, some scientists don’t like to share their data on it. So it’s hard to find quality data to feed into the algorithm.”

To get around these issues, Cai began working with data from other skin diseases, such as melanoma, as a way to teach his algorithm the basics of what unhealthy skin looks like. He is now fine-tuning the technique to get the algorithm to hone in on autoimmune blistering diseases.

“One hundred percent of the image entry is manual,” says Cai. “I have to crop all the images and adjust them and do quality checks.”

Along the way, Cai has gotten to bounce ideas off Ay and LJI Postdoctoral Fellow Abbas Roayaei Ardakany, Ph.D. “They’ve been really, really helpful with my project,” says Cai. “This is one of my first experiences working with professors and postdocs, and it’s been really eye-opening.”

There’s a lot more to be done, but Cai has shown that this limited-data kind of machine learning can help identify diseases like his mom’s pemphigus vulgaris. Someday, Cai wants this algorithm to be scalable and to serve as a backbone for identifying many rare diseases.

Right now, Cai is deciding where he wants to attend college. He hasn’t decided what to major in, but he knows he wants to work in the sciences. He’s written a paper on his algorithm and shared it to medRxiv. Cai is also happy to report that his mom’s disease is in remission.

“It could have been a lot, lot worse,” says Cai, “and my goal is to help those patients who are less fortunate.”