Every virus has a distinct shape. Some viruses look like spiky balls. Other viruses look like alien space ships.

Ebola virus looks like a twisted shoelace. Its looping, filamentous structure is why it belongs to the “Filoviridae” family of viruses, which also includes the deadly Marburg virus.

Kelly Shaffer is a UC San Diego Biomedical Sciences graduate student and a member of the Saphire Lab at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI). She’s investigating how human antibodies bind to filoviruses to prevent severe disease.

“Vaccines and therapeutics are urgently needed in regions where multiple filoviruses co-circulate and laboratory diagnostics are limited,” says Shaffer.

Now Shaffer has been awarded the 2026 BioLegend Graduate Fellowship in Immunology, which will provide $25,000 toward her stipend (salary support), tuition, and fees as a UC San Diego Biological Sciences graduate student. This prestigious fellowship is granted by the Program in Immunology, a joint initiative of LJI and UC San Diego.

With this support, Shaffer will move forward in her hunt for “cross-reactive” antibodies that can neutralize multiple filoviruses at once.

Fighting filoviruses

Without treatment, up to 90 percent of Ebola virus cases are fatal. Marburg virus can also kill up to 90 percent of its victims, and there’s some evidence it may be even deadlier than Ebola virus. These are hemorrhagic fever viruses, which means that, along with severe flu-like symptoms, victims can experience severe internal and external bleeding.

“I really can’t think of a worse way to die from a virus,” says Shaffer.

The new fellowship allows Shaffer to build on a filovirus research project she launched earlier this year with support from LJI’s Tullie and Rickey Families SPARK Awards for Innovations in Immunology, funded by the generosity of LJI Board Director Barbara Donnell, Bill Passey, and Maria Silva, and various donors.

Shaffer’s project is very personal. Shaffer has visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo twice and worked closely with doctors and scientists who have been on the front lines of deadly viral outbreaks. Some of her collaborators are Ebola infection survivors themselves.

She’s also seen how tough it is to conduct research in rural communities and underfunded laboratories. “I have personally had to navigate political unrest, lack of reliable electricity, and limited resources while trying to run experiments in the field,” says Shaffer. “My journey in this field has been more than just technical training—it has been profoundly motivating on a personal and professional level.”

Ebola and Marburg virus have evolved to evade our antibody defenses. Luckily, the human immune system is constantly adapting to combat new threats. Shaffer’s research highlights the rare human antibodies that neutralize several filoviruses at once.

Through a collaboration with UC Los Angeles in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Shaffer has access to blood samples from a rare group of Congolese volunteers. Some of these volunteers are survivors of Ebola virus infection, while others—such as healthcare workers—have lived in conditions where filovirus exposure was likely.

Shaffer came up with a plan to learn from these filovirus survivors. Her goal was to see if their samples contained antibodies that might be powerful enough to fight both Ebola virus and Marburg virus.

“These are some of the only specimens of their kind in existence,” says Shaffer. “I hypothesize that these individuals’ immune systems hold rare clues to broad protection, and that examining their antibodies could uncover defenses never seen before in single-exposure studies.”

Uncovering powerful antibodies

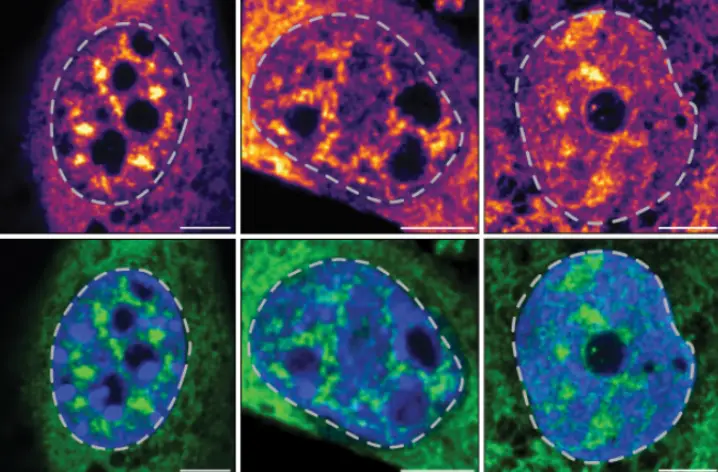

Shaffer’s SPARK award supported her efforts to run these precious blood samples through a powerful piece of equipment called the Beacon Optifluidic Platform. The Beacon identifies antibodies that target key viral proteins. Each match between an antibody and a virus target is known as a “hit.”

Shaffer began by analyzing a blood sample from a survivor of the 1995 Ebola virus outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The results left her stunned. From this one sample, Shaffer got hundreds of “hits” that bound to both Ebola and Marburg. Even more amazing: until now, a “panfilovirus” antibody had never been found.

Each of these “hits” represented an antibody that recognized an important piece of the filovirus structure: the glycoprotein.

Picture a snake. Now imagine that snake is bedazzled in knobby little proteins. Those are the glycoproteins, and they are key to filovirus infection. Filoviruses use their glycoproteins to fuse with host cells and establish infections.

Shaffer’s research revealed a whole pack of antibodies that can wedge themselves in that viral machinery and potentially stop filoviruses in their tracks.

Expanding a critical study

Shaffer now plans to run samples from more filovirus survivors through the Beacon. She hopes scientists can use her findings to develop antibody therapeutics to treat multiple kinds of filovirus infections. Her work may also lead to vaccines that trigger the body to produce the same protective antibody response.

Shaffer is encouraged to see the outpouring of support for her filovirus project. “We call these ‘neglected’ tropical diseases because they’re neglected. They’re not thought about much,” she says. But viruses travel. In the end, a “pan-filovirus” vaccine could stop outbreaks in Central Africa and guard against wider, global outbreaks.

“My work has underscored the importance of collaboration across disciplines, cultures, countries, and laboratories,” says Shaffer.