Scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) and researchers at the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center have discovered a new way to redirect virus-fighting T cells to kill pancreatic tumor cells. In a new study, their experimental approach led to decreased tumor growth and longer survival in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer.

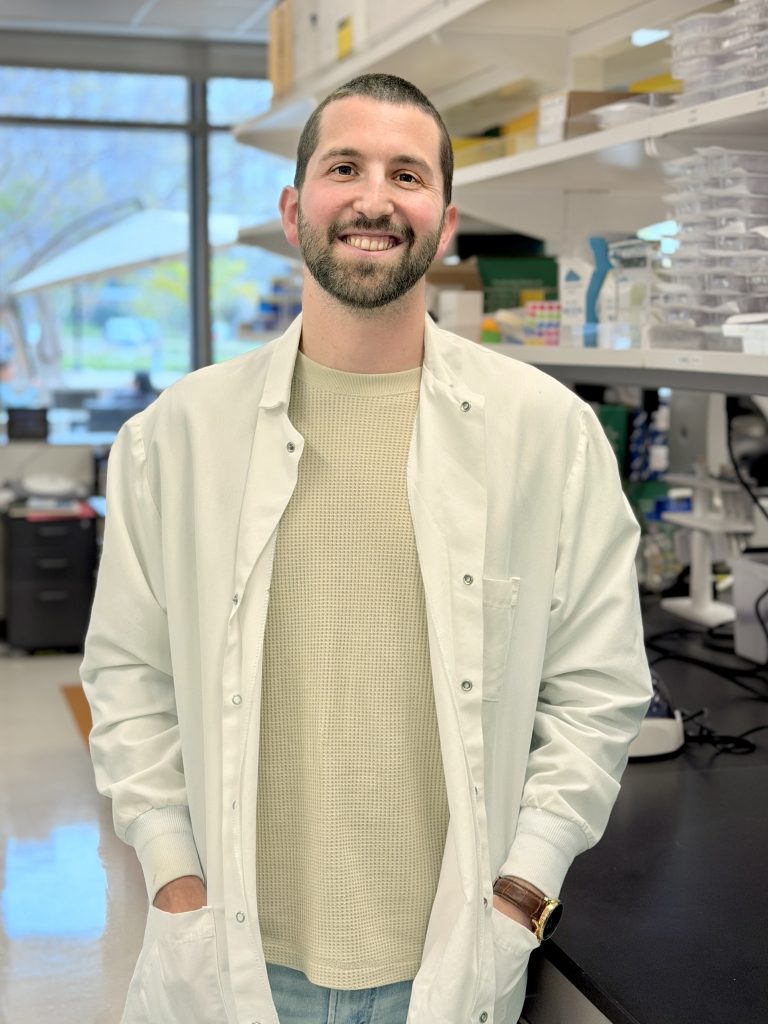

“Pancreatic cancer is a super tough cancer to treat, both in humans and in mouse models of cancer,” says study co-senior author Chris A. Benedict, Ph.D., LJI Associate Professor. “So we started with the hardest tumor, and we saw an impact.”

“We were thrilled to see such a strong response in our preclinical studies,” says co-senior author Tatiana Hurtado de Mendoza, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

Pancreatic cancer has one of the lowest five-year survival rates out of any cancer type. Unlike other cancers, pancreatic tumors contain very few mutations, which allows them to blend into surrounding tissue. In fact, scientists call pancreatic tumors immunologically “cold” because the tumors don’t attract cancer-killing immune cells.

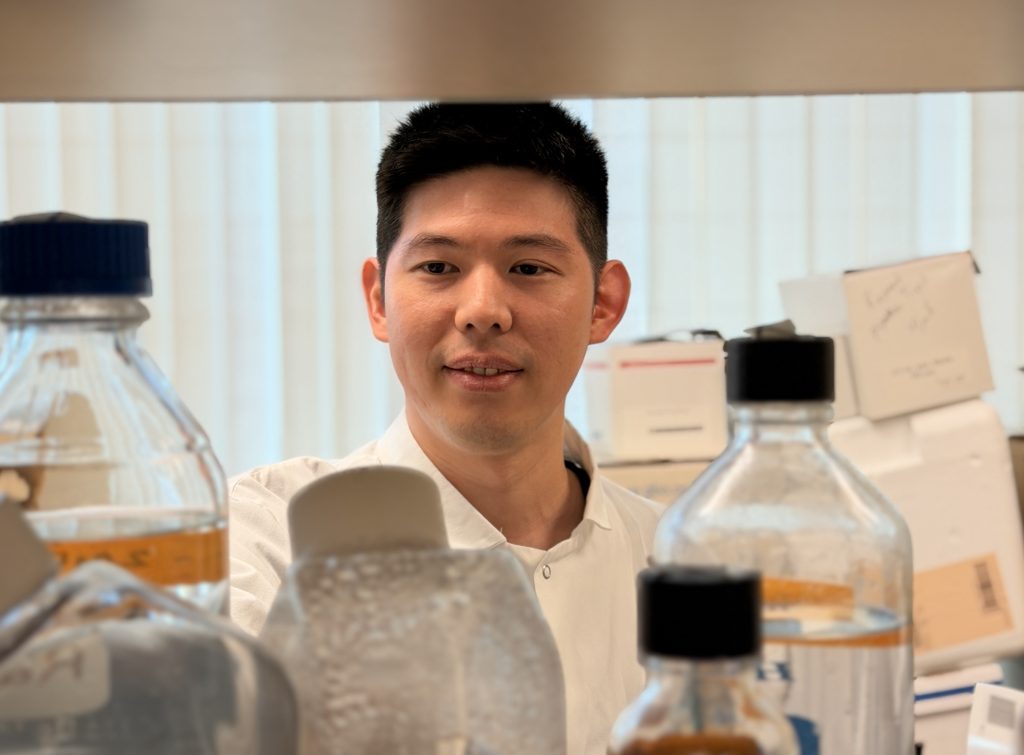

“Some tumors have plenty of mutations, which facilitate their recognition and targeting by the immune system,” says study co-first author Remi Marrocco, Ph.D., a Postdoctoral Fellow at LJI. “Pancreatic cancer, however, has fewer mutations and therefore very few spontaneously infiltrating T cells.”

The new research, published recently in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, shows how scientists can use markers from viruses to turn pancreatic cancers from “cold” to burning hot.

Calling immune cells into battle

The researchers took advantage of a fascinating phenomenon: immune cell memory.

Every time you get sick, your body develops “memory” immune cells. Some of these “memory cells” are T cells, which can spend months or years patrolling your tissues for molecules, such as viral peptide molecules, that suggest the pathogen has returned.

For the new study, the researchers injected mice carrying pancreatic tumors with peptides from a virus called cytomegalovirus (CMV). For most people, CMV is completely harmless. The virus spreads through bodily fluids, such as saliva and urine, and infection is very common in children. Following infection, CMV lays latent in the body for a person’s whole life. Here in Southern California, around 50 percent of people carry CMV.

Most people don’t notice CMV infection—but their T cells sure do. Following an initial CMV infection, the body builds up a huge army of memory T cells that scan the body for signs that CMV is causing trouble.

“Our approach was to harness cells that we have in our bodies already. In this case, we harnessed T cells that recognize cytomegalovirus, also called CMV,” says Benedict. “The idea was to repurpose these T cells and get them to start killing the tumor.”

A promising treatment approach

The plan worked.

“By delivering small pieces of viral proteins—CMV peptides—to pancreatic tumors, we were able to re-direct the virus-specific T cells against the cancer cells,” says Hurtado de Mendoza.

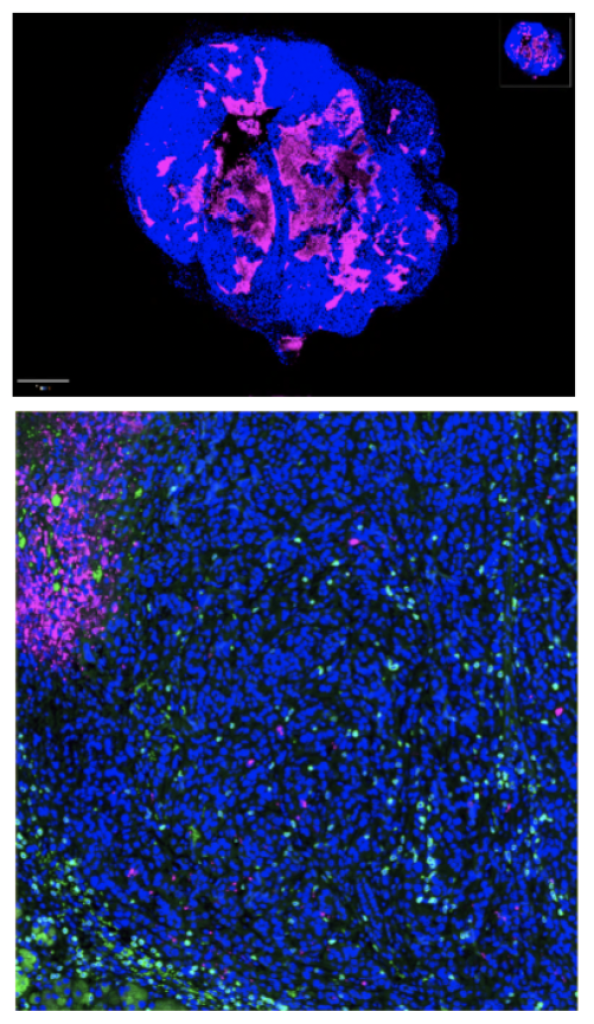

When testing their approach in mice with a previous CMV infection, the researchers found:

- Mice treated with CMV peptides experienced significantly delayed tumor growth.

- Treated mice survived 42 days compared with 25 days for control mice, a 70 percent increase in survival.

- The therapy was effective at a well-tolerated dose, with minimal toxicity observed.

- Though the treatment was given by a systemic injection, CMV-specific memory T cells preferentially recognized and targeted the tumors during treatment with no damage to other organs.

- The treatment changed the gene expression profile of tumor cells, making them more sensitive to immune cell attack.

“This therapy represents a significant step forward in the fight against pancreatic cancer, and we’re hopeful that it could provide new treatment options for patients with limited alternatives,” added co-first author Jay Patel, Research Assistant at UC San Diego. “CMV-specific T cells have the potential to become a powerful tool in the fight against cancer, and we’re only just beginning to unlock their possibilities.” [Read the UC San Diego School of Medicine press release]

The researchers are also exploring the potential of their approach to treat other challenging cancers. Benedict and Hurtado de Mendoza recently received a Curebound Discovery Award to investigate the possibility of using CMV-fighting T cells to combat triple-negative breast cancer.

Hurtado de Mendoza is currently working to hone humanized mouse models that take into account a person’s specific immune responses to CMV. To translate this discovery to human health, the scientists can rely on a pool of 200 new human CMV peptides, recently discovered by the Benedict and Sette Labs at LJI. These peptides have the potential to re-energize CMV-specific human T cells to target pancreatic cancer.

“This approach has the potential to be tumor-agnostic, meaning it could be effective against a range of cancer types, including breast cancer, lung cancer, and others,” says Hurtado de Mendoza. “We’re excited to explore its potential in humanized mouse models to bring it one step closer to clinical trials.”

Additional authors of the study, “Redirecting cytomegalovirus immunity against pancreas cancer for immunotherapy,” included Jay Patel, Rithika Medari, Philip Salu, Eduardo Lucero-Meza, Catarina Maia, Simon Brunel, Alexei Martsinkovskiy, Siming Sun, Kevin Gulay, Malak Jaljuli, Evangeline Mose, and Andrew Lowy.

This research was supported by the Foundation for a Better World (grant 001) and the National Institutes of Health (grants R21CA286198, AI139749, and AI101423).