Zika

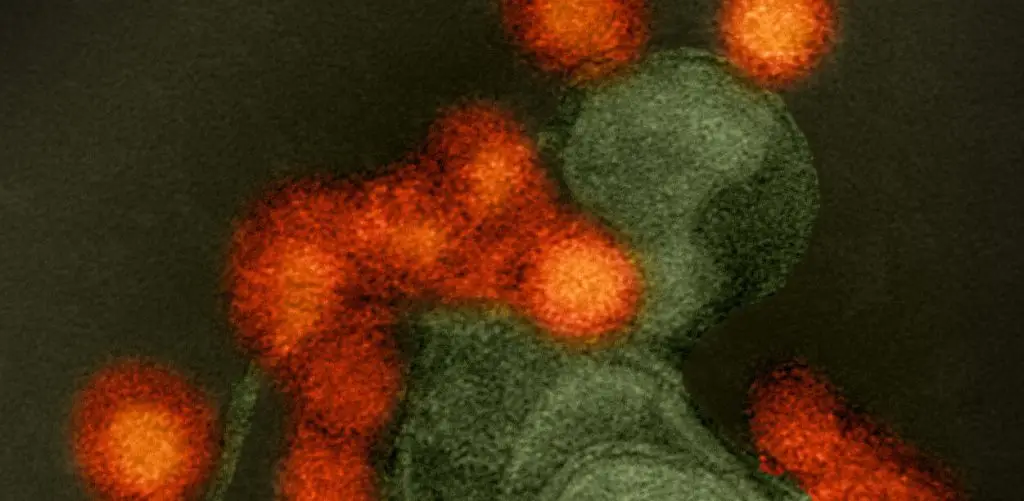

Zika is caused by a flavivirus similar to dengue virus and is endemic in many of the same tropical and subtropical regions. Zika (and dengue) viruses are transmitted via A. aegypti or A. albopictus mosquitoes, but Zika can also be transmitted sexually in semen and to a fetus during pregnancy. In adults, Zika symptoms can appear quite mild and cause symptoms such as fever, rash, joint and muscle pain and conjunctivitis.

However, infection in fetuses and infants can be devastating. Around 5 to 10 percent of babies born to mothers infected with Zika exhibit catastrophic Zika-associated birth defects, among them microcephaly and Guillain-Barre syndrome, an immune attack on nerves that can cause paralysis. Currently there is no anti-Zika vaccine available.

LJI scientists are making great strides in solving the mysteries of flaviviruses—how seemingly mild conditions become catastrophic and how immunity to one can trigger reactivity to another. This knowledge is essential in order to engineer a vaccine. LJI scientists have also recently shown that Zika infection could have long-term effects on the brain.

Our Approach

The flavivirus fundamentals

LJI Professor Sujan Shresta, Ph.D., has developed mouse models of Zika virus infection and has used them to monitor immune responses to viral infection, screen vaccine candidates or anti-Zika drugs, and explore a paradoxical cross-reactivity scenario unique to flaviruses known as antibody dependent enhancement, or ADE. In ADE, the presence of antibodies recognizing one flavivirus triggers a lethal inflammatory response to a related flavivirus. In one widely-cited experiment, Shresta showed that newborn mouse pups harboring anti-Zika antibodies were more vulnerable to death from dengue exposure than mice that lacked anti-Zika antibodies.

Shresta’s mouse models also formed the basis for a collaboration with Rockefeller University investigators showing that neural progenitor or “stem” cells in brains of adult mice are targeted by the Zika virus and when infected undergo cell death and decreased proliferation. This suggests that Zika infection may inflict damage on the adult brain in ways that only become apparent years later, such as memory loss or depression.

In 2022, Shresta uncovered a major clue to how Zika virus attacks human cells. Her research showed that when Zika virus enters human dendritic cells, they turn these immune cells into lipid molecule factories. The virus then uses these lipids to build copies of itself, which go on to infect new host cells.

A pan-flavivirus vaccine

LJI’s research and expertise in Zika and dengue virus infections is already guiding vaccine efforts. Shresta recently piloted a DNA-based anti-Zika vaccine that elicits a protective T cell response in mice. She is now taking this research to the next level by developing a pan-flavivirus vaccine that elicits protective antibody and T cell responses against all four dengue serotypes and Zika. If successful, this approach would circumvent issues related to harmful cross-reactivity between these viruses and represent a major step toward the first universal anti-Zika and anti-dengue vaccine strategy.

In 2020, her lab showed that antibodies against JEV are “cross-reactive” and can also recognize Zika virus. Unfortunately, these antibodies can actually cause ADE and make Zika cases more severe. The research, conducted in mice, was the first to show that T cells can counteract this dangerous phenomenon. “This means we probably need to be developing a vaccine against both viruses that can elicit a good balance of antibodies and T cells,” Shresta explained. In a study later that year, the Shresta Lab published additional evidence that effective Zika vaccines need to activate T cells to work alongside antibodies.

Further flavivirus questions

LJI Professor Alessandro Sette, Dr. Biol. Sci., who is known for his work studying the role of T cells in the immune response to dengue virus, is expanding his interests to Zika and asking whether immune cells activated in prior flavivirus infections can cross-react with Zika virus. Sette and LJI Professor Bjoern Peters, Ph.D., and LJI Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand, M.D., Ph.D., are identifying components of the virus particle most likely to elicit an immune response. Their work was the first to characterize the human CD8+ T cells that respond to Zika infection.

Learn more:

Related News

- Research News

- Institute News

- Research News