Asthma

Asthma is more dangerous than many people realize. An estimated 10 Americans die everyday from asthma, and the disease leads to around 439,000 hospitalizations and 1.3 million emergency room trips each year. Asthma affects over 200 million people worldwide.

During an asthma attack, patients experience bronchial spasms that obstruct the airway. These respiratory symptoms are usually caused by the immune system’s overreaction to allergens, but asthma can also be induced by physical activity.

There is no cure for asthma: patients cope with the disease by avoiding allergens or activities that trigger it. Many patients with asthma rely heavily on inhaled or oral corticosteroids to open airways in case of asthmatic attack. Still, some severe forms of asthma do not respond to these common treatments.

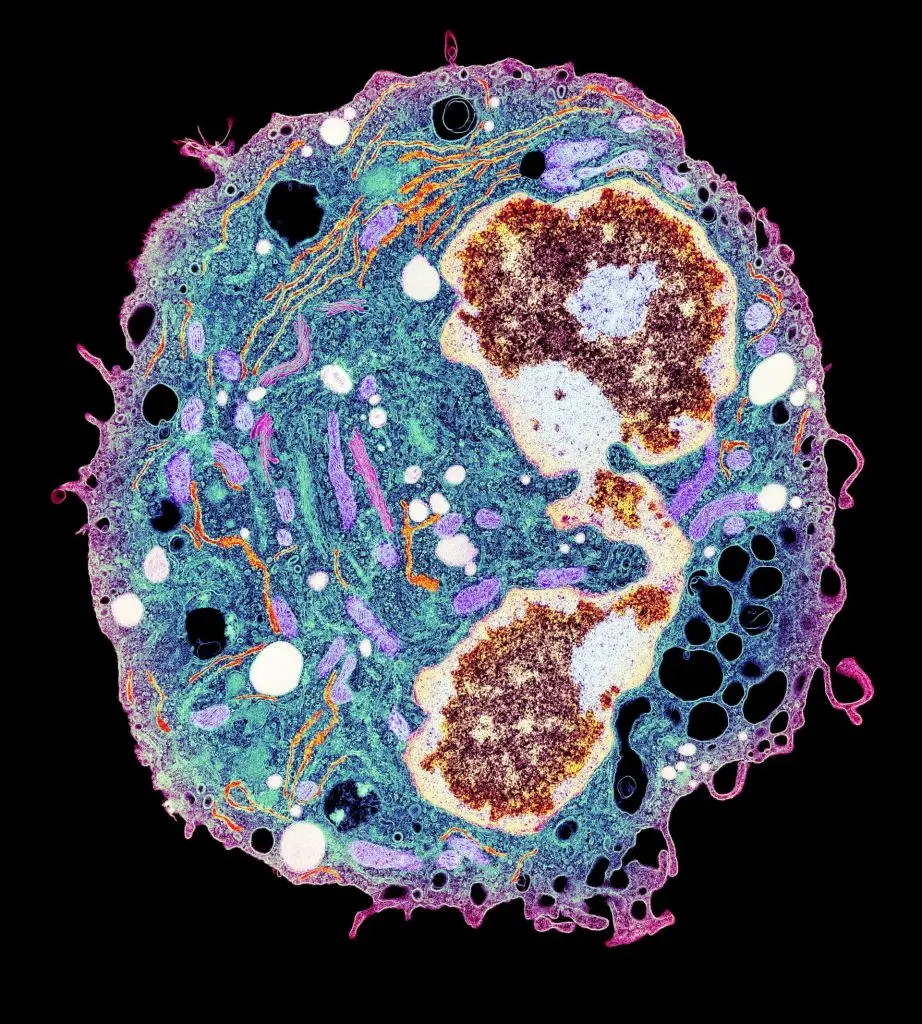

Patients with asthma routinely show high levels of inflammatory “Th2 cytokine” molecules in their bloodstream. These molecules are secreted by immune cells called Th2 helper cells. These messenger molecules exacerbate asthma and other allergies. Ample evidence supports the idea that heightened Th2 cell signaling is the cellular signature of allergy and asthma.

Researchers are hopeful that Th2 cytokines may prove a useful target for new asthma drug therapies, and recent studies suggest some patients with hard-to-treat asthma may benefit from monoclonal antibody therapeutics that targeting Th2 cytokines. Today, several LJI investigators are searching for genes or proteins that either foment or subdue Th2 cell activity in affected patients.

Our Approach

Genome-wide analysis

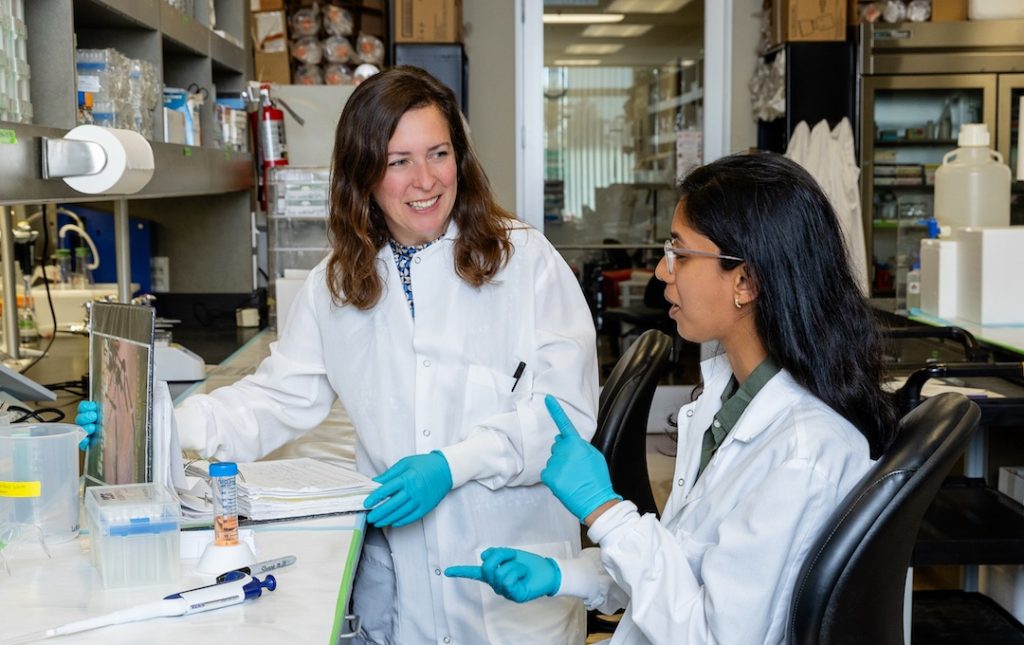

LJI Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand, M.D., Ph.D., recently applied next-generation computational approaches to take a global snapshot of gene expression in both Th1 and Th2 cells. To do so, he surveyed the entire genome of both asthmatic and control non-asthmatic individuals for short stretches of DNA called enhancers, which switch target genes on and off. This analysis, conducted with LJI Professors Bjoern Peters, Ph.D., and Anjana Rao, Ph.D., identified a manageable number of genes inappropriately switched on in Th2 cells of asthmatic patients, factors that could potentially serve as novel therapeutic targets.

In the lab of LJI Associate Professor Ferhat Ay, Ph.D., researchers are using advanced bioinformatics tools to analyze immune cell data to find any asthma-specific biomarkers. This work, a collaboration with the Vijayanand Lab, may shed light on why some people are more vulnerable to severe asthma than others—and why life-saving therapies don’t work for all patients.

Sex-based differences in asthma

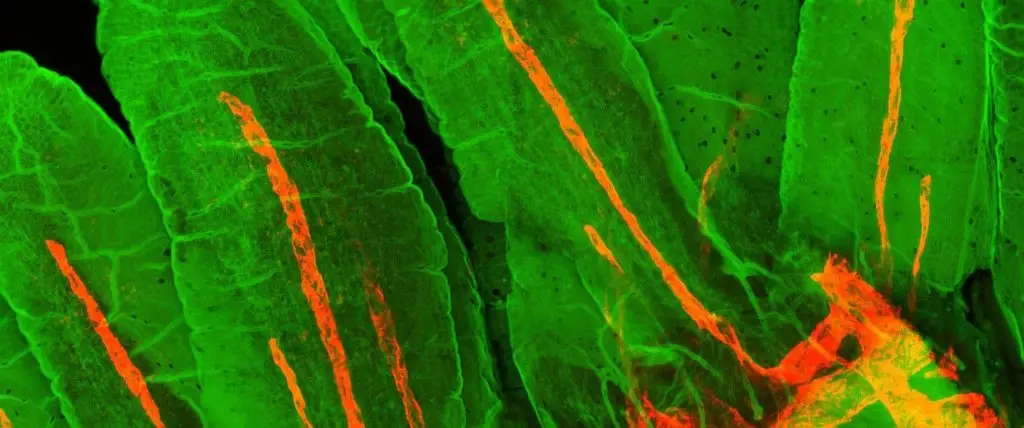

In a 2023 study, Dr. Vijayanand and colleagues tracked down a population of immune cells that appear to drive severe asthma in men who develop the disease after age 40. These cells, called cytotoxic CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells, gather in the lungs, where they vastly outnumber the immune cells that are meant to keep dangerous inflammation under control.

These findings give scientists a “biomarker” to help them detect cytotoxic CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells in more patients. Going forward, the researchers are interested in investigating why these harmful T cells appear more common in men with severe asthma.

New ways to stop inflammation

LJI scientists have also highlighted the importance of the immune system’s mast cells, which release histamine, the molecule that actually causes asthma symptoms. During his career at LJI, Professor Emeritus Toshiaki Kawakami, M.D., Ph.D., discovered that a pro-inflammatory protein called histamine-releasing factor (HRF) activates a receptor expressed on mast cells, causing them to release histamine. His lab went on to identify two peptides that can block HRF activity and decrease airway inflammation in mouse models of asthma.

In 2023, Dr. Kawakami published an important study into the molecular drivers of severe asthma and rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbation (a type of asthma that can accompany a common cold). His findings, published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, suggest people with both types of asthma may benefit from therapies that block interactions between HRF and antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE).

Turning off LIGHT

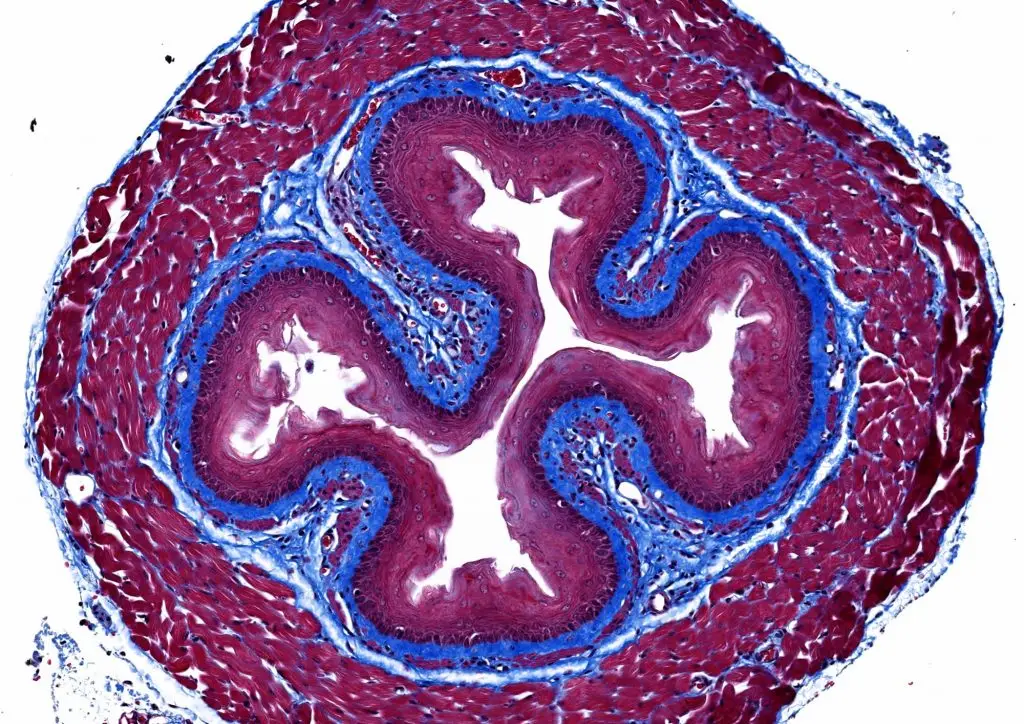

LJI Professor Michael Croft, Ph.D., is working to counteract airway wall thickening and tissue scarring, known as fibrosis, seen in asthmatic patients. For more than a decade, Croft has studied the role of a protein called LIGHT, which is a type of inflammatory “cytokine” produced by the immune system’s T cells. T cells normally fight disease, but in asthma, T cells overreact to environmental triggers and flood the airways with LIGHT and other inflammatory cytokines.

Croft’s research has shown that LIGHT continues to cause damage once an asthma attack is over. Croft has found that LIGHT is essential in a process called tissue “remodeling,” where the lungs and airways grow thicker following an asthma attack. These thicker airways can leave a person with long-term breathing problems.

In 2022, Croft published a pivotal study showing that therapeutics to stop LIGHT could reverse airway and lung damage in patients—and potentially offer a long-term treatment for asthma.

Investigating hypoxia

Hypoxia is a brief period where a person cannot breathe properly. Experiencing hypoxia is a known trigger for developing and worsening lung conditions such as severe asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and fibrosis. To treat and prevent these diseases, researchers need to understand why a lack of oxygen would affect the immune system. In a 2022 study, LJI Professor Mitchell Kronenberg, Ph.D., showed that hypoxia can activate the same group of immune cells that cause inflammation during asthma attacks. As a person with gasps for breath, these cells flood the airways with molecules that damage the lungs, paving the way for long-term lung damage. The research team also showed that human lung epithelial cells exposed to hypoxia produce a molecule called ADM. This means ADM or its receptor could be targets for treating inflammatory and allergic lung diseases.

Learn more:

Related News

- Immune Matters

- Research News

- Institute News

Research Projects

Selected References Grégory Seumois, Ciro Ramírez-Suástegui, Benjamin J. Schmiedel, Shu Liang, Bjoern Peters, Alessandro Sette, Vijayanand P (2020). Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of allergen-specific T cells in allergy and asthma. [...]

The Vijayanand lab has a strong interest in understanding the role of T cell enhancers (epigenetics players) in asthma, developing cutting-edge tools to study enhancer function, and utilizing these [...]

Pediatric Milk Allergy: To study the frequency and phenotype of milk allergen-specific T cells in cohorts with different disease manifestations and define molecular markers of disease status and progression to [...]