“SPARK is a very valuable program. For a young investigator like myself, it was important to develop a project with autonomy, to test a risky hypothesis, and to practice managerial functions such as working with a relatively strict time frame and budget. I also learned a lot about public speaking and communicating science to a lay audience. I enjoyed my interactions with donors and it was very energizing to get to know people from the public who are interested in our science.”

What if a person’s insulin-producing beta cells are orchestrating their own demise?

Funded: January 2022

Funded By: The generosity of Barbara Donnell and Denny Sanford

What was the goal of your SPARK project?

Type 1 diabetes (T1D), an autoimmune disease that usually affects young people, is on the rise worldwide, and to date there is no cure. We still do not completely understand the underlying processes that drive the dysfunction and destruction of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. One of the questions raised in the last few years is whether beta cells are orchestrating their own demise by causing a direct response in the immune cells around them. My hypothesis is that beta cells can affect the behavior of immune T cells around them.

Did you face any challenges?

My experiments went really well. I was able to optimize most of the techniques and get preliminary data to ask for follow-on funding. The main obstacle I encountered is that I need more time and funding to perfect the staining experiments and the 3D image analysis strategy, and also to repeat the experiments to get more solid data (I need to verify that my findings are replicated in multiple donors).

SPARK project results:

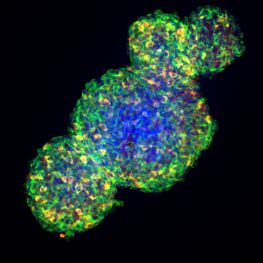

I successfully conducted the experiments, using both human pancreatic islet spheroids (a 3D in vitro platform of “perfect islets,” that helps us to study and recreate some of the processes that happen in T1D) and human isolated native islets.

I co-cultured human islets (spheroids and native) with immune cells (CD4+ T cells) under different conditions. I studied the interaction between the immune cells and the islets with a special focus on the insulin-producing beta cells using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry.

I found that when immune CD4+ T cells are in a resting state (not activated), they are less prone to infiltrate the islets, and they do not affect the capacity of the islet beta cells to secrete insulin. Instead, when immune (CD4+ T cells) were activated, they infiltrated the islet and caused some impact in the islet function. On the other hand, once again I confirmed our previous findings showing that pro-inflammatory cytokines (proteins secreted after infections or during local injuries, that can stress the islets) induce the expression of proteins in the islets such as HLA class I and HLA class II. These proteins are important because, in principle, they allow the islet beta cells to communicate directly with the immune system. Activated CD4+ T cells increase the expression of HLA class I by the islets co-cultured with these activated CD4+ T cells. This is relevant, because other immune cell types (like CD8+ T cells) can detect these HLA class I proteins and launch an additional immune response. Those findings suggest that the immune cells on the pancreas of patients with T1D are probably locally activated, and for that reason are more prone to invade the islet and make it dysfunctional.

Even one specific immune cell type seems to be able to induce changes in the beta cells, which can culminate in an orchestrated immune response (by implicating other immune cell types around it). In our field, it is critical to understand whether type 1 diabetes is primarily triggered by the beta cell itself or by the immune system—and to understand the chronology of the events in the human pancreas. This knowledge will drastically change future therapeutic approaches.

What’s next for this project?

I plan to continue this project. With my SPARK award, I learned that CD4+ T cells are able to infiltrate the islet when activated and that having enough of these cells can induce HLA class I expression in the islet, which can have important implications in T1D. Additionally, I improved some technical aspects that are innovative and relevant when asking for further funding. With early preliminary data, I submitted a career award from Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and an R01 grant to continue with the project. Unfortunately, I didn’t get funded in the first cycle, but I received constructive feedback and now I have more data, so I plan to apply for those grants again.

What’s next for Estefania?

I recently got an R01 from the NIH and I am launching my independent research career in academia. I will need more funding in order to be successful in academia, so I plan to continue applying for grants. My next career step is to become an Assistant Professor.